To Laugh in a Special Way

Or as a sneer. This week’s message comes by way of an Estonian word for laughter I was struck by irvitamina which is close enough to vitamina which loosely correlates with vitamins in many Romantic languages. But in thinking of this, I became fixated on Estonian poetry, as one is want to do, and found myself digging in.

First, I entered with this quote from George Ivask who did a good summarizing effort detailing the mid-late 20th-century Estonian poets, many of whom were translated and mentored by a singular individual - a comparative literature professors Ants Oras. The quote from “Eight Estonian Poets,” is as follows, “Of the eight poets translated by Ants Oras, five chose exile, three remained in Estonia. One of these three died prematurely, one has been deprived of all outlets for publication, and one is strictly limited in her freedom of poetic self-expression. The new generation of poets in Soviet Estonia has no striking talents.”

When I was casually reading this essay, upon getting to the line the new generation of poets in Soviet Estonia has no striking talents, I quite earnestly choked in laughter. Critics are such beautifully funny individuals in this way. Prepared to or perhaps incited to give such sweeping statements, and yet how can one profess to make such a claim confidently? I think of so many athletic comparisons and how most professional athletes have said - regardless of sport - that there are prodigies in far-off countries whom have never seen a professionalizing spotlight and whose talents would put them to shame. Of course, this draws an implicit conclusion that poetry is a talent which I’m not sure I’m ready to make. Instead, I’ll continue by offering you the humorous examination I made of this Ivask’s claim.

I did not tell you of my laughs last week and I won’t make an attempt at covering the history lost. I apologize. Some of them I simply don’t remember. But, here, some more offerings and prostrations. This past week I met with another Seattle poet and literature enthusiast, Katie, to talk bears. During which I confessed my bold take: that there are too many people trying to be traditionally published authors with regard to poetry; that there is not enough encouragement and instruction that one may simply write a poem and share it with their friends and loves ones and there is no real need to submit this work to journals; that the business of poetry does a poor job of encouraging the communal aspect of poetry in opposition to the competitive-publishing model of poetry. It feels especially wrong of me to hold this opinion considering I host a poetry-reading series and desperately wish to make of myself an exception - to be a traditionally published author. But nevertheless in sharing it, oh did I laugh. Perhaps this is my own form of no striking talent style criticism.

Returning to Estonia, first, from Eleanor Soekõrv in “The Slavic and East European Journal,” there is a documentation of the sheer numbers we’re talking.

According to the Database of Estonian Literature, which has been monitoring translations from Estonian in to other languages since 2001, the amount of translated works into English has increased from two books to a striking twenty-one books issued in 2018, the average of recent years being approximately seven books per year, as opposed to eight per decade up until the restoration of Estonian independence in 1991. However, the canon of Estonian literature in English is fragmented, and benefits immensely from anthologies with historical accounts, such as Bird's An Introduction to Estonian Literature: they seek to destroy the marginality of peripheral literature by enabling readers to get acquainted with Estonian culture, as opposed to isolated translations that maintain a vacuum effect.

Let’s do some quick math. Eight per decade up until 1991 would be around 40 total works, and with the accredited average per year since, we can add in an approximate 160 for a total of 200 works translated into English.

For additional numeric context, I’ve read about 100 books of poetry a year for the last ten years or so. Which would mean to read the entirety of Estonian poetry translated into English, if I were really setting my mind to it, I could tackle it in a year, but more comfortably in two years.

Another laugh for you: I’ve taken up my joy of a weekly semi-competitive soccer league I’m playing in. In one of my recent games, within two minutes of playing, I took a deflected ball to the face. Well, adjacent to the face: it hit directly the bridge of my glasses, and didn’t suffer my skin much of any marring. Instead, the glasses, perfectly hit, snapped in half. For the first half of the game, I attempted to play with an athletic-taped construction; however, because of the way they snapped, this tape would not hold. Then, me and my -6.00 correction nearsightedness played half of a game where I was thanking my lucky stars that the soccer ball we were using was a hot pink against the otherwise dark green grass of the field. I could see little more than vague blurs of people moving around. This was, legitimately, incredibly fun. I don’t consider myself as having been particularly effective or competitive in my play, yet, I do love forced changes to perspective - to view a field in a new and unique perspective. Did you know your eyes are, prescriptively, titled Dexter and Sinister?

Part of the reason why I enjoy international literature or literature-in-translation so much is because it provides guideposts like this for which I can lose direction and replace it with something of an uncovering mission. It is one thing to read an Estonian poet, like Marie Under, who I’ll quote below, and think, huh, interesting poem. It is another to read Estonian Poet Marie Under, knowing she was nominated for the Nobel in Literature some thirty-odd times, never winning, and was the founder of several Estonian literary groups which then offshooted or grew into literary societies that continue to today or birthed their own contemporary traditions of literature.

Denunciation

I cry aloud with all my people’s mouths,

our land is smitten by a plague of fear and lead,

our land is shadowed by the gallows tree

our land a common graveyard, huge with dead.

Who’ll come to help? Right here, at present, now!

Because the patient’s weak, has lost his hold.

But, like the call of birds, my shouting fades

in emptiness: the world is arrogant and cold.

The sighing of the old, the baby’s cry —

do they all run to sand, illusion, fail?

Men, women groan like wounded deer

to those in power all this is just a fairy-tale.

Dark is the world’s eye, its ear is deaf,

the powerful lost in madness or stupidity.

Compassion’s only felt by those whom suffering breaks,

and sufferers alone have hearts like you and me.

translated by Ilmar LehtpereI don’t think this historical or biographical knowledge necessitates a unique perspective in reading the poem. But a poem like “Denunciation,” does beg to be placed within the context of what might be being called against — in this case, a proclamation against occupations by Soviet and Germanic armies, the culturally repressive government of Soviet Estonia that occupied the country until its independence granted in 1991. In this way it seems poignant that a poet who could write a line like the world is arrogant and cold hails from a country with a language with a special word for a sneering type of laughter.

Heather and I finished watching the Dimension 20 series A Starstruck Odyssey, a live-play campaign based on the play and comic series Starstruck by dungeonmaster Brennan Lee Mulligan’s mother, Elaine Lee. What an utter joy of a game to watch, and without spoiling any details for those of you who wish to watch it, it has given me a new phrase from which I long to revolve around: the ball is rolling up.

I don’t know anything about linguistic study, but I offer the below paragraph on Estonian phonetics by Eva Liina Asu and Pire Teras. I think it adds depth and dimension to translation choices knowing that the same word can mean entirely different things dependent on syllabic-stresses.

For vowels, the three-way durational opposition occurs only in the first syllable of a word, which as a rule carries the primary stress, as for example in the triplet: kalu [kahr] (Ql) 'fish (part, pl.)', kaalu [kailu] (Q2) 'scales (gen. sg.)', kaalu [kaulu] (Q3) 'scales (part. sg.)'. For consonants, the opposition operates between the first and second syllable of a disyllabic sequence, e.g. kala [kokr] (Ql), 'fish', kalla [kalla] (Q2) 'calla lily', kalla [kalila] (Q3) 'pour (imp. 2nd sg.)'. As can be seen from these examples, contrastive quantity marks differences in both lexical meaning and grammatical function. All monosyllabic words, e.g. saad [saut] 'get (pres. 2nd sg.)' are according to traditional grammar treated as overlong.

This passage I then wish to pair with Ants Oras, aforementioned scholar, who also provided some of the earliest translations of Marie Under, in his essay, “Marie Under and Estonian Poetry,” in the Sewanee Review:

It would take real genius to render in another language the full strength, compression, and boldness of these verses—their accumulation of discord turned into concord, the transcendental quality of their vision, first of darkness, then of blinding light, with a sense of movement present everywhere. In the poems of release and liberation there often is, in addition, serenity, not quietistic but active, constantly on the point of becoming jubilant.

…

The spirit of Estonian poetry remains alive. It is questionable, however, to what extent it would do so but for the feeling of continuity created by some presiding figures from before the exodus.

In a similar fashion of laughter, I think it is hysterical to use the passive third-person to discuss how translating Marie Under would take “real genius,” when the author writing this line literally translated Marie Under.

I hope you enjoy my dive into Estonian Literature. I’ll leave you with these last notes:

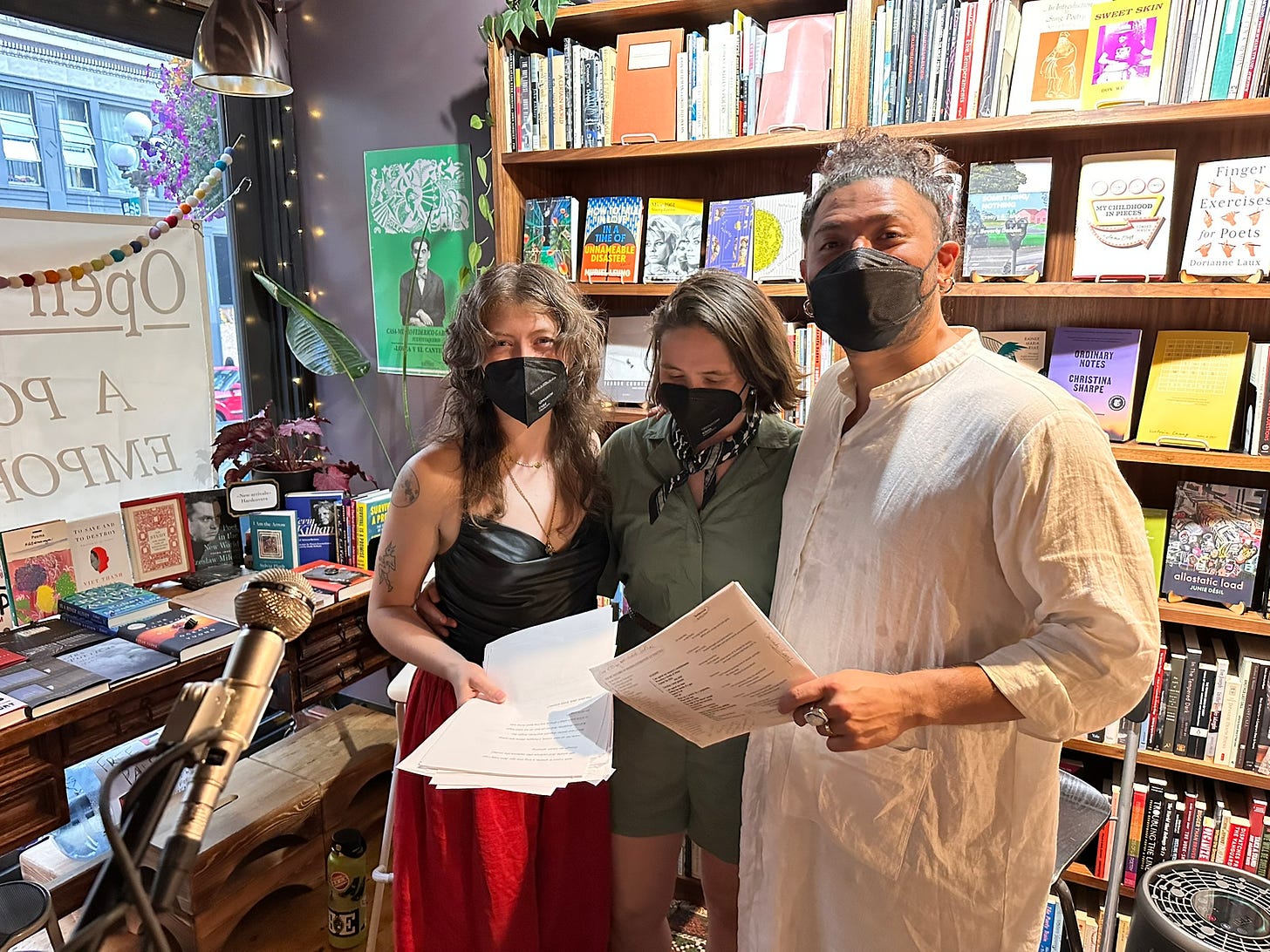

Ally and I held our seventh (!! so biblical) Other People’s Poems with delightful readers Sullivan Forderhase, Dujie Tahat, and Shelby Handler. While I try not to hold favorites, each reading seems to add successive waves of connection that I cannot help but be profoundly affected by. People hanging outside the store after the reading, making plans with each other and getting each other’s numbers. We had someone reach out to tell they met their partner at an OPP reading. There’s an OPP reading group which meets regularly. I am so lucky to take part in this community - to make spaces and to encourage the social of literature. Readership is a blessed gift.

And I performed my first poetry reading in seven(!! so biblical) years. This was an event in collaboration with poet-artist Zachary Schomberg’s exhibit of paintings titled Two Women on the Shore inspired by the Edvard Munch painting of the same name. And, as a treat, I was captured on camera being a joyful individual. What a gift to be viewed with such radiance.